Image credit: King-Wai Yau Laboratory

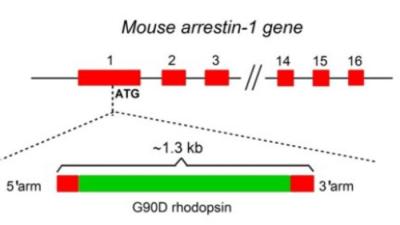

In what they believe is a solution to a 30-year biological mystery, neuroscientists at Johns Hopkins Medicine say they have used genetically engineered mice to address how one mutation in the gene for the light-sensing protein rhodopsin results in congenital stationary night blindness. The condition, present from birth, causes poor vision in low-light settings.

The findings demonstrate that the rhodopsin gene mutation, called G90D, produces an unusual background electrical “noise” that desensitizes the eye’s rods, those cells in the retina at the back of the eye responsible for nighttime vision, thus causing night blindness.

The identification of the unusual electrical activity could “provide future targets for therapeutic interventions,” the study’s authors write.

When comparing the low expression level of G90D found in genetically engineered mice versus the level of G90D found in human patients with this night blindness, the authors concluded that unusual electrical activity with a low amplitude but extremely high frequency may be the greatest contributor to the disease in people.