By Adam Korengold ~

Data visualization is a new and quickly evolving discipline. While the modern form of the practice often uses complex IT tools, the practice of using charts, graphs, and visual imagery to uncover data’s meaning is not new. With a collection spanning from the eleventh century to the present, the National Library of Medicine (NLM) holds many examples of how medicine and science have used visuals to communicate insights.

A Brief History of Data Visualization

The first popular graphical statistician was William Playfair, a Scottish political economist whose 1786 Commercial and Political Atlas visualized economic data. Seventy-five years later, the London physician John Snow created what may be the first, and most influential, medical data visualization. Amidst a cholera epidemic in the early 1850s, and a tension between using statistics for pattern recognition only, and using data as part of a methodological approach, his map fundamentally changed how clinicians, researchers, and the public use data.

Courtesy Wellcome Library

Based on data that he had gathered from his own research, Snow created a map showing the locations of fatal cases in relation to where water pumps were located.

Visualizations in the NLM Historical Collections

Here are several ways that pieces in NLM’s digital collections visualize data for showing research insights, mapping, and public health.

At the most basic level, data visualization illustrates research findings for diverse audiences. One of the best examples of this comes from the extraordinary career of Florence Nightingale, and her study of deaths in British military hospitals during the Crimean War, titled “Diagram of the Causes of Mortality in the Army in the East.”

National Library of Medicine #101598842

Dating from the same period as Snow’s cholera map, Nightingale’s rotary diagrams show the difference between deaths from wounds and other injuries (in red), and the much greater scale of deaths from preventable causes, such as cholera and other communicable diseases. This visualization was also instrumental in advancing medical practice in times of war.

Process and the scientific method are also an essential part of medical practice. Sometimes the most insightful data visualizations do no more than show how scientists achieved a particular objective, providing documentary evidence of how modern genetics came to be. A prime example comes from the noted geneticist Marshall Nirenberg. Nirenberg was able to decipher how DNA sequences direct the body to assemble amino acids.

Profiles in Science, National Library of Medicine

The resulting code chart (Marshall Nirenberg Papers, 1965) is made of six pieces of graph paper taped together. Columns are labeled for each of the amino acids, and each one of the genetic codes is noted down the left margin. The chart shows numerous edits—so it serves as a living document of the founding days of molecular biology.

Maps are sometimes the ideal way to visualize data because they apply a data set to a physical structure. Similarly to John Snow working with cholera, the Paris city statistician, Jacques Bertillon, published a major study of the prevalence of influenza, including visualizations of infection and death by age and geographic location, in 1892.

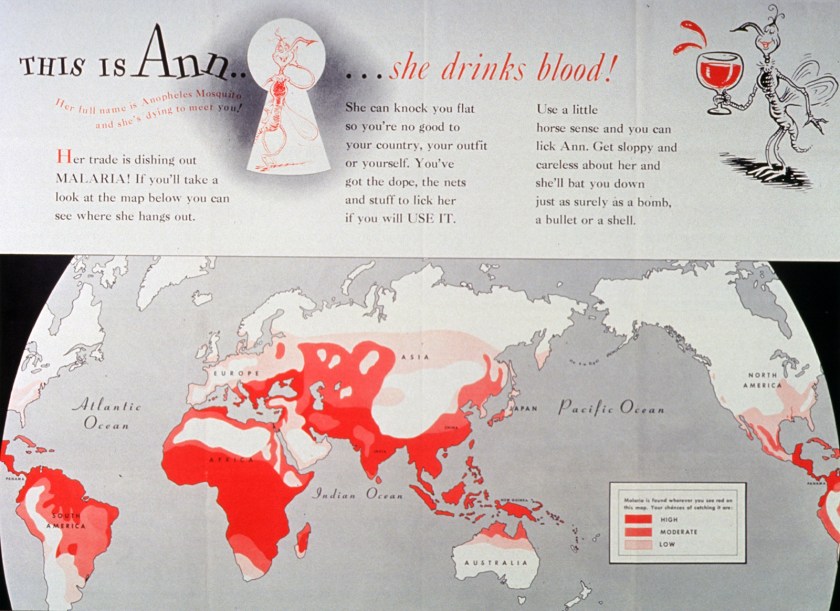

Maps can use a familiar structure, like a map of the world in 1943, showing the prevalence of malaria, titled “This is Ann… she drinks blood!” (Special Service Division, Army Service Forces, War Department: U.S. G.P.O., 1943). A mosquito-borne disease, malaria was a particular problem in North Africa and southeast Asia during the Second World War, where Allied troops were fighting.

National Library of Medicine #101439358

This visualization uses shades of red to show intensity of malaria infection, clearly meant for a wartime audience. The framing device is Ann the anopheles mosquito, whom eagle-eyed readers will recognize as the creation of no less than Theodore Geisel, more widely known as Dr. Seuss.

Maps aren’t always geographic. This example titled “The Human Genome Map ” (American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1990), is one of the first visualizations of the human genome. It is hard to understate the value of the full map of the human genome to the right, which is the basis for so many advancements in medicine and health over the past three decades.

National Library of Medicine #101449383

It’s useful to visualize public health information in ways that are easy to understand and not limited to language or level of data literacy. NLM’s collection includes visualizations that serve the public interest and speak to issues of public health, like this Soviet-era poster titled “Malaria: Severe Contagious Disease.” It shows the fluctuating fever that is a hallmark of the disease (USSR Central Institute of Sanitary Education, 1942). At that time, Russian troops fought (literally) feverishly to repel the Nazi invasion. As we saw in the Dr. Seuss map above, southern Russia, where much of the fighting took place, was also an area of concern for malaria.

National Library of Medicine #233259671

The headline reads “Malaria-Severe Contagious Disease.” The clearly uncomfortable patient in the main illustration shows how debilitating and exhausting that malaria, and the graph is a useful piece of messaging to convey an essential feature of malaria for an audience of clinicians, patients, and the public to understand a disease with which they may not otherwise be familiar.

Similarly, this example of the relationship between taxes on liquor, and per capita consumption (Koller, 1929) between 1919 and 1922 shows, in clear visual terms, that higher taxes are associated with less drinking per person in Great Britain, Belgium, Germany, France, and Switzerland.

National Library of Medicine #101449729

How to Find Visualizations in NLM’s Digital Collections

It’s easy to find visualizations in NLM’s digital collections. The simplest way is to use your Web browser to navigate to https://collections.nlm.nih.gov. From the dropdown menu, choose “still images,” and then use the search box to specify the types of information of interest, like maps, visualizations, diagrams, or specific topics of interest like influenza, HIV, or the human genome (See the diagram below).

Beyond their value in documenting how medical science has shown its findings visually, these examples help today’s medical researchers to make their findings more resonant for the people they serve.

Explore other data visualizations, both modern and historical in our Revealing Data series, which explores what researchers from a variety of disciplines are learning from centuries of preserved data, and how their work can help us think about the future preservation and uses of the data we collect today.

Adam Korengold is an Analytics Lead in NLM’s Office of Computer and Communications Systems. He works with NLM staff to analyze and visualize data about how the library’s digital products are reaching audiences. He also teaches in the graduate Data Analytics and Visualization program at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, Maryland.

Adam Korengold is an Analytics Lead in NLM’s Office of Computer and Communications Systems. He works with NLM staff to analyze and visualize data about how the library’s digital products are reaching audiences. He also teaches in the graduate Data Analytics and Visualization program at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, Maryland.

Discover more from Circulating Now from the NLM Historical Collections

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One comment